The Ideas Have ‘Left the Building’

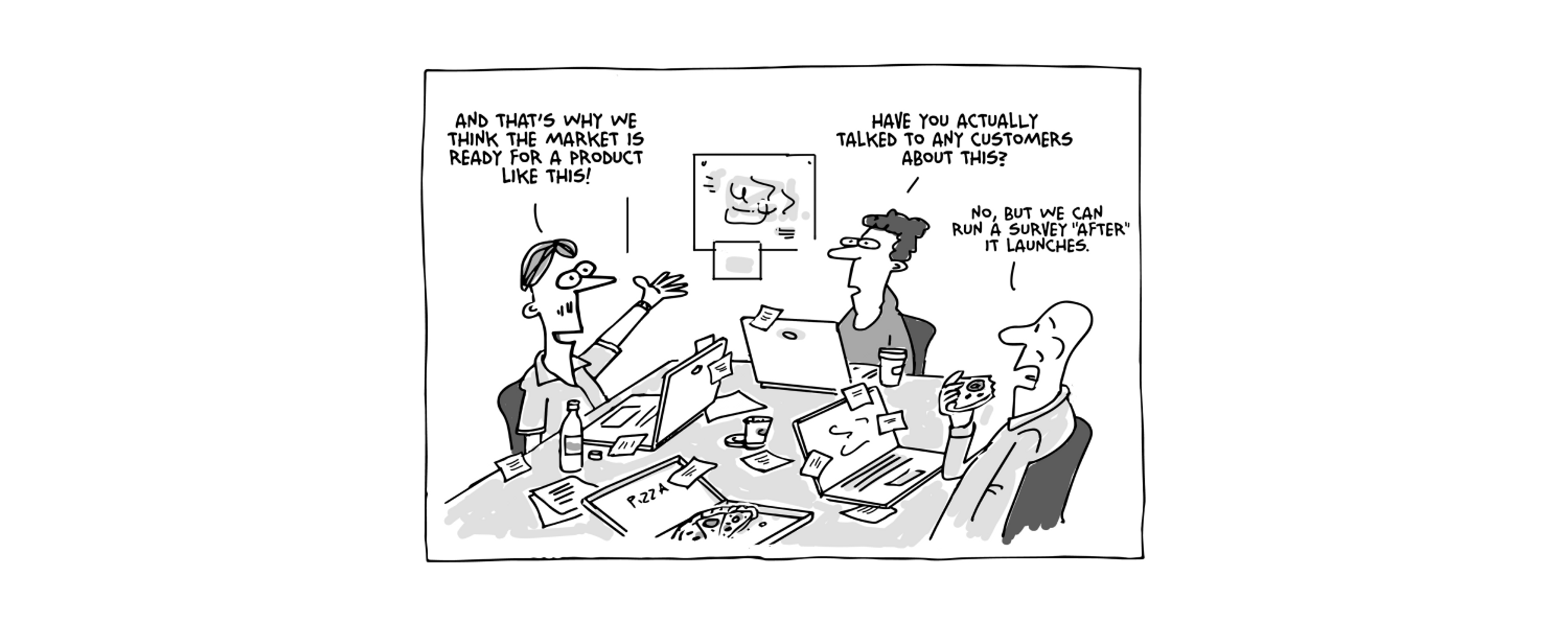

The above cartoon illustrates a classic approach to ideation: a product development team falls so deeply in love with its own idea that it forgets to ask users and customers if it answers any real needs. It’s a trap many companies fall into and a major reason why 70% to 90% of new products fail to gain traction in the marketplace.

For innovation consultants and product development teams there is no shortage of great ideas. What’s often missing is a customer who is willing to pay for them.

What looks like a great idea to you may not look that way to a customer

Innovation consultants have tended to trade on their ability to create the kinds of breakthroughs that clients are unable to easily create by themselves. In a 1999 HBR article by Eric von Hippel, Stefan Tomke and Mary Sonnack, the authors lamented that “Unfortunately, the development groups at many companies don’t deliver the goods. Instead of breakthroughs, they produce mainly line extensions and incremental improvements to existing products and services.” Which is why they bring in someone from outside who is not encumbered by the day-to-day operation of the business, and is able to ‘think outside the box’.

Trouble is, thinking outside the box often happens inside a box – the one occupied by consultants and their clients as they develop ideas. It can be a very creative and exciting box. It’s a box where eureka moments can happen. But it is nonetheless a closed world.

You need to take your ideas out of the ’box’ and validate them with users and customers. While this seems self-evident, it took the Silicon Valley experience of entrepreneur and now Stanford professor of entrepreneurship Steve Blank to articulate it in his book Four Steps to the Epiphany.

Assuming you agree with Steve, where do you start and who do you start with? Let’s say you are a major consumer packaged goods company with a product that once dominated its category but has declined significantly as its customer base ages out of the market. To attract a younger customer, you need new product ideas. You can sit in a room with your consultants and think up new product ideas. Or you can go find young users and shop with them, cook with them, and dine with them. Get up close and personal, so to speak. In this way you not only learn what needs and preferences are not being met by the market, but what they are doing to meet them for themselves.

These people are what the above-mentioned Eric von Hippel calls ‘lead users’. They are passionate enough about something – could be food, or sports, or music – to invest their own time, energy and money in solving for their unmet needs. It’s an elite form of DIY.

The user is not always the customer

Von Hippel famously tells the story of how kayaking went from a niche sport to a $100 million industry. Back in the 90s, a small group of what are called ‘rodeo kayakers’ could be found on the rivers of Tennessee, Georgia and the Carolinas shooting the rapids in homemade boats. Boat makers started building molds right next to the rivers where the kayakers were and used that opportunity to iterate with them on a weekly basis. As a result there were 3 or 4 new kayak products on the market every season.

But while they were developing the product for rodeo kayakers, they weren’t looking at the wider market of light users – the customers who just wanted a paddle around the lake. The rodeo kayaker market was soon saturated. To grow the business, manufacturers would need to go beyond the power users to find and create new customers.

The important point to remember here is that the user is not necessarily the same thing as a customer. If there were a wider market for these boats, the manufacturers would need to find a potential customer, iterate until that customer liked it enough to pay for it, which is to say until the product satisfied the light user’s needs, and then find enough customers to justify growing the business in a meaningful way.

The best ideas come from those closest to the problem

This notion of getting out of the office to test and validate your ideas with customers is what Steve Blank calls the customer development process. It unfolds in four stages: customer discovery, customer validation, customer creation and company building. Discovery focuses on product/market fit: whether or not the product solves a customer problem or need. Validation develops a sales model that can be replicated. Creation is about driving end-user demand. And company building is about transitioning from learning to execution at scale.

When he looked back at his storied career in the start-up world, Blank realized that a venture’s success only came when the idea had achieved product/market fit. That was the real eureka moment. And that moment is critical because it provides the evidence needed to justify further rounds of funding.

The customer development model espoused by Blank, linked with von Hippel’s concept of the lead user is a demonstration of the truth that no matter how great you think your ideas are, the best ones always come from those who are closest to the problem: users and customers. Until you validate both your product and your business model with them, until you have evidence of product/market fit, your idea is just an idea.